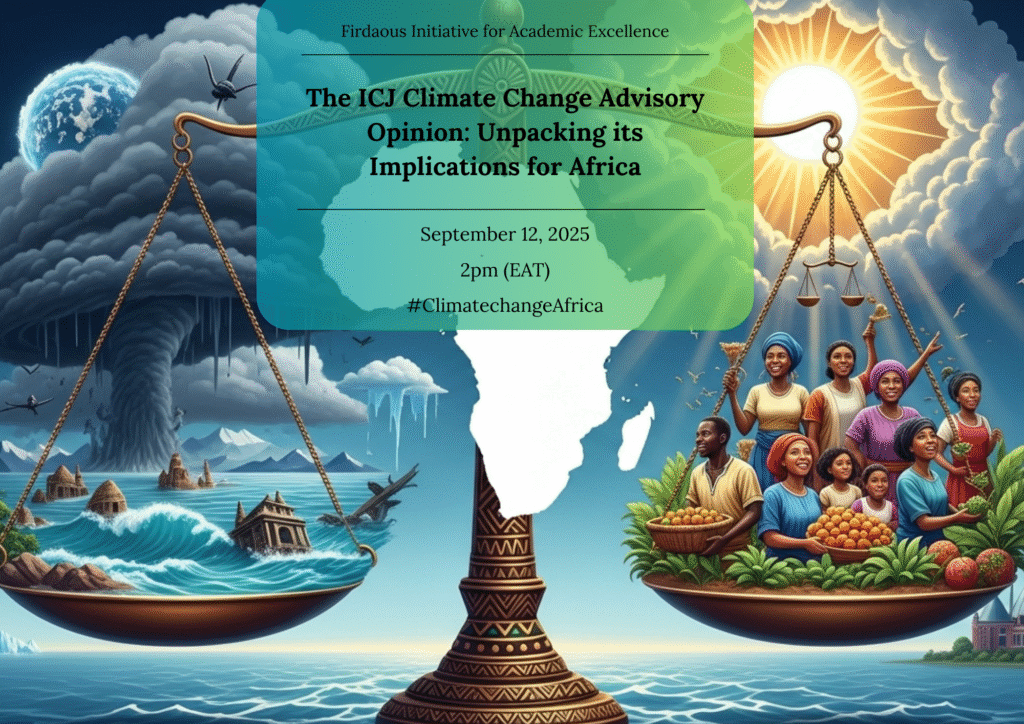

Date: September 12, 2025

1. Executive Summary

The ICJ Climate Change Advisory Opinion, delivered on July 23, 2023, represents a “game-changer for human rights” and a “monumental victory” for climate justice, particularly for Africa. The opinion characterizes climate change as an “urgent and existential threat” and provides an authoritative interpretation of states’ existing climate obligations under international law. Key findings include the legal binding nature of the Paris Agreement’s 1.5-degree temperature limit, clarification of state responsibility for climate inaction, and a strong emphasis on the intrinsic link between environmental protection and human rights. For Africa, which disproportionately suffers from climate impacts despite being a low contributor to emissions, this opinion provides a powerful legal tool to hold industrialized nations accountable, drive adaptation and mitigation efforts, and inform future legal strategies.

2. Main Themes and Key Findings of the ICJ Advisory Opinion

The ICJ Advisory Opinion addresses several critical areas, establishing a new legal landscape for climate change governance:

- Climate Change as an Urgent Threat: The Court unequivocally characterizes climate change as “an urgent and existential threat.” This underscores the severity and immediacy of the crisis, demanding robust and legally binding responses from states.

- Legally Binding 1.5-Degree Temperature Limit: While the Paris Agreement is based on voluntary commitments, the ICJ considers the “1.5 degree temperature limit under the Paris Agreement as a legally binding target.” This is a highly significant finding, transforming a political goal into a legal obligation.

- State Obligations for Mitigation and Adaptation: The opinion “articulates states obligations regarding the mitigation of and adaptation to climate change and clarifies state responsibility for climate inaction.” This means states have a legal duty to take measures to reduce emissions and adapt to the unavoidable impacts of climate change.

- Climate Change as a Human Rights Issue: A crucial general point made by the Court was “to treat, climate change is not only in environmental issue, but also an important human rights issue.” This re-frames climate action from solely an environmental concern to a fundamental human rights imperative. The Court recognized that a “clean healthy and sustainable environment is a precondition of the enjoyment of many human rights such as the right to life the right to health and the right to inadequate standard of living including access to water food and housing.”

- Due Diligence Obligation: The Court emphasized “the standard of utilities as a primary measures of, you know statements.” This “stringent form of due diligence” applies both under the Convention on the Law of the Sea and international human rights law, with the opinion demonstrating “that these obligation of due diligence and the boss, the Law of the Sea and under international humanity, a human rights law is not different, but rather it is, you know the same.”

- Duty to Cooperate: States have an obligation “to cooperate and to find equitable solutions” to address the impacts of climate change, particularly for vulnerable nations.

- Non-Refoulement Principle and Climate Mobility: The Court affirmed that “the principal of Non-raformant applies to protects people displaced across borders in the context of climate change.” The ICJ quoted: “the Court considers that conditions resulting from climate change which are likely to endanger the lives of individuals, may lead them to seek safety in another country or prevent them from returning to their own in the view of the court states have obligations under the principle of modern formal where there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of a reperable harm to the right to life in breach of Article 6 of the ICCPR if individuals are returned to their country of origin.” This means individuals facing “serious harm… connected to impacts of climate change alone or together with other events are entitled to protection under human rights.”

- Sovereignty and Statelessness for Low-Lying States: The opinion recognized “implications for the rights security and sovereignty. Estates due to the disappearance of territory.” Significantly, the Court stated that “once a state is already established, the disappearance of one of its constituent elements would not necessarily entail the loss of statehood,” which “could have implications for Conceptions of citizenship and statelessness in the future.”

- Marine Environment Protection: The opinion linked “environmental protection and human, rights and of course with a significant focus on the impact of sea level rise.” It highlighted the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, obliging states to “prevent you know, marine pollution,” describing this as a “stringent form of due diligence.” The failure to prevent “greenhouse gas emission from having the marine environment, it is also concurrently failing is duty to be able to protect its people from foreseeable, human rights harm on climate change.”

3. Implications for Africa

The ICJ Advisory Opinion holds profound and multifaceted implications for African nations, which are uniquely vulnerable to climate change impacts despite their minimal contribution to global emissions.

- Amplifying Climate Justice Demands: The opinion “provides a powerful legal to be able to amplify the long held African position on climate justice, which emphasize this storyful are responsibility and the principle of common but I differentiated responsibility.” This strengthens Africa’s moral and political arguments with legal backing.

- Legal Basis for Accountability: The opinion transforms climate action from a “moral or a political argument” into a “legal obligation,” offering African states “a more solid foundation to be able to hold industrialized nations accountable” for their historical emissions and ongoing impacts.

- Validation of Lived Realities: By linking climate change to human rights, the opinion “validates the life… the reality is basically of millions across, you know, the African continent who already first devastating consequences,” such as recurring droughts in the Horn of Africa, intensifying water scarcity, and food insecurity, directly threatening the “right to life, food, water.”

- Protection of Vulnerable Populations: The Court recognized the “specific. and potentially more severe. Impacts of climate change on the enjoyment of rights of particular, groups of people. So women children indigenous peoples and people in vulnerable situations generally.” This provides a legal basis for specific protections for these groups in Africa.

- Addressing Climate Mobility: The reaffirmation of the non-refoulement principle is critical for African states facing increased cross-border displacement due to climate change. It obligates states not to return individuals to life-threatening harm connected to climate impacts, potentially influencing refugee and complementary protection frameworks.

- Marine Environment and Coastal Communities: For coastal African nations, the opinion’s focus on sea-level rise and its human rights consequences is particularly relevant. It strengthens the obligation to protect fishing communities and other coastal populations whose livelihoods and cultural heritage are threatened by environmental degradation and rising seas.

- Catalyst for African Legal Development: The ICJ opinion serves as a crucial precedent for the anticipated advisory opinion from the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Experts anticipate the African Court will “reflect on and build on the ICS Advisory opinion. And potentially go further,” offering “greater specificity than the ICJ” due to Africa’s “unique human rights and refugee protection landscape.” This could influence regional legal frameworks, such as the Kampala Convention and OAU Refugee Convention, in addressing climate-induced displacement.

- Informing Climate Finance Negotiations: The Court’s emphasis on states’ “duty corporate and to be able to find equitable solutions” can be interpreted as a mandate for increased “finance for the adaptation” in Africa. This re-frames adaptation finance not as “a charity basis, but naturally… a situation of just Because of the effect that arise.”

- Future Legal Strategies: African legal scholars and practitioners are encouraged to translate the ICJ opinion into long-term strategies. This involves creating “a frame pattern of schedule” for discussions and “legal surgery” on the judgments, highlighting problems and possible solutions, and engaging the public and policymakers. There is a call for an “African and African and developed system in terms of litigation, in terms of a bookish and terms of our legal system that will fit into Africa.”

4. Challenges and Future Directions

While offering significant opportunities, implementing the ICJ’s guidance in Africa faces challenges:

- Diverse Legal Systems: Africa’s legal landscape is “diverse and complex,” mixing common, civil, customary, and Sharia law traditions, which can complicate the uniform application of international legal principles.

- Lack of Awareness and Political Will: Historically, there has been a lack of “much awareness by the people” regarding their legal rights against governments, and policymakers have not always been “brought to book.”

- Resource Constraints: Legal aid and judicial systems in many African countries are “strangulated with lack of funds,” hindering access to justice, particularly for marginalized groups.

- Balancing Development Priorities: African states must balance their international legal obligations with local development priorities, especially when drafting policies for internal displacement and migration.

- Emergence of AI: The advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in legal systems presents both opportunities for “increased efficiency” and “improved accuracy” but also risks if not carefully managed. Experts warn against “foolishly following AI” and advocate for African-specific “chatters” to guide its ethical and responsible use.

To overcome these challenges and leverage the ICJ opinion effectively, future directions include:

- Investing in Legal Technology Infrastructure: African countries should “invest more in legal technology infrastructure” to modernize their legal systems and enhance access to information and justice.

- Developing Local Solutions: It is crucial to “develop, local solutions” that fit African contexts, rather than merely borrowing and copying foreign systems.

- Strengthening Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR): ADR mechanisms like arbitration, negotiation, and conciliation should be “testified” and promoted to offer cost-effective and efficient means of resolving disputes.

- Enhancing Judicial Independence and Accountability: Protecting the rule of law, promoting fairness, and supporting democracy are vital. This requires “judicial training,” establishing “judicial conduct commissions,” and fostering “transparency and openness.”

- Promoting Access to Justice: This includes strengthening legal aid systems and ensuring their adequate funding, alongside fostering “legal literacy” and “public interest litigation.”

- Intensifying Regional and International Cooperation: African Union treaties and regional economic communities must “be intensified” to promote legal harmonization and collaboration on climate justice and development goals.

- African Legal Scientific Approach: There is a call for African nations to “put heads together and do what is called an African And African legal scientific approach” to address legal challenges and opportunities unique to the continent.

Our Esteemed Speakers

- Cleo Hansen-Lohrey (Lecturer, University of Tasmania, Australia

- Swaleh H. Wengo (Human Rights & Marine Environment PhD Candidate, University of Cape Town, South Africa)

- Prof. Abiodyn Amuda-Kannike SAN (Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria)

For more information please contact:

Alessia Tesoro